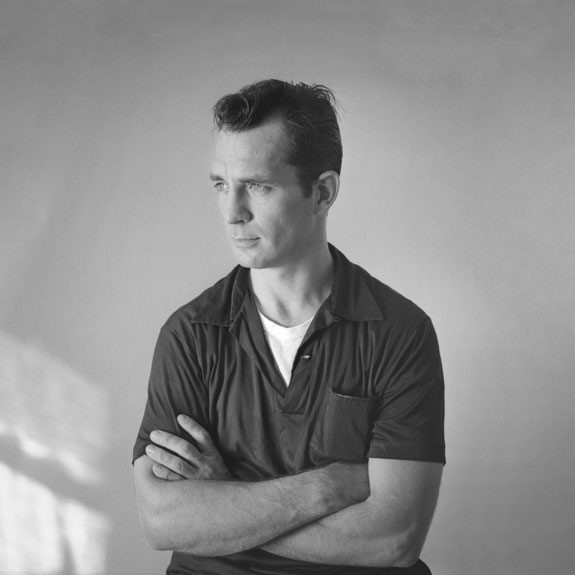

JACK KEROUAC Centennial Birthday Event Schedule Announced via THE JACK KEROUAC ESTATE & KEROUAC @ 100 COMMITTEE

DT: JANUARY 20, 2022 FM: KELLY WALSH, SRO PR THE JACK KEROUAC ESTATE AND KEROUAC @ 100 COMMITTEE SHARE SCHEDULE OF EVENTS FOR CENTENNIAL BIRTHDAY CELEBRATION FOR FAMED NOVELIST, WRITER, […]